X-rays are a viable part of

medicine today and have been used in clinical medicine and for experimental

purposes in physics since their discovery in 1895. The value of X-rays to

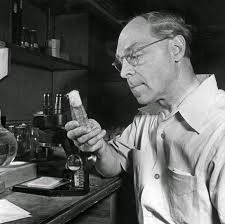

genetics research only became apparent however when Hermann Muller used

radioactivity to produce point mutations in the fruit fly Drosophila. Muller was

an American geneticist known for his demonstration that mutations and hereditary

changes can be caused by X-rays affecting genes and chromosomes. His work on

the mutating abilities of X-rays won him the Nobel Prize for Physiology or

Medicine in 1946.

Hermann Joseph Muller was born

December 21st, 1890 in New York and died April 5, 1967. He grew up

in Manhattan and after graduating high school in 1907 at the age of sixteen,

Muller attended Columbia University and was attracted to the emerging field of

genetics. He was interested specifically in the physical and chemical nature

and operations of genes. Muller also continued his graduate education at

Columbia and spent time in T.H. Morgan’s infamous Drosophila lab. Muller along

with other students in the lab, took part in stealing milk bottles from

apartment steps in order to house the fruit flies.

During his time in the Fly Lab,

Muller published a paper demonstrating the effects of mutations in one gene on

the expression of other genes, implying that many fly characteristics depended

on the interaction of several genes. However, Muller clashed with Morgan and

his other students, particularly Alfred Sturtevant, feeling that he was not

fully acknowledged and that his ideas weren’t fully represented in the papers. Due to his quarrels with members of the lab,

Muller left in 1915 after obtaining his degree.

Muller continued his studies

involving the molecular, physical, and chemical natures and operations of genes

and their resulting effects on gene expression to demonstrate during the 1920s

that X-rays could induce mutations. This discovery won him fame and then later

contributed to his winning of the Nobel Prize.

In 1926 at the University of

Texas, Muller exposed male fruit flies to high doses of radiation to then let

them mate with virgin female fruit flies. Muller was able to artificially

induce more than 100 mutations in the offspring. Some of the mutations were

deadly others were not lethal but visible in the offspring. Muller concluded

that radioactivity had the ability to reach chromosomes to affect the molecular

structure of individual genes leaving them either inoperative or altering their

chemical functions.

Muller’s paper “Artificial

Transmutation of the Gene” published in 1927 provided only an outline of the data

but he presented at the International Congress of Plant Sciences to create a

media sensation. He used his fame from his discovery to caution against the

indiscriminate use of X-rays in medicine. Despite his adamant warnings, some

physicians continued using high amounts of X-rays and some even continued to prescribe

X-rays to stimulate ovulation in sterile women.

Muller also was known for his strong

and often outspoken views on socialism, which got him in trouble with the

administration while working at the University of Texas. He collaborated on a

Communist newspaper at the University resulting in the FBI tracking his

activities. Muller decided to leave for Europe in 1932 during the Depression

and moved to the Soviet Union in 1934.

Initially Muller was happy with

the progressive Communist society in the Soviet Union, however he quickly grew

unhappy as Stalin’s police state attacked genetics by pushing the Lamarckian

ideas of evolution. The state dictated who could work in his lab and

interrogated him for referring to the work of Germans or Russian emigres.

Muller eventually left the Soviet Union in 1937 and spent eight weeks in Spain

helping the International Brigade develop a method of obtaining blood from

recently killed soldiers to use for transfusions. He then moved again, this

time to Scotland and worked at the University of Edinburgh continuing with

X-rays and other mutagens like UV and mustard gas.

Initially Muller was happy with

the progressive Communist society in the Soviet Union, however he quickly grew

unhappy as Stalin’s police state attacked genetics by pushing the Lamarckian

ideas of evolution. The state dictated who could work in his lab and

interrogated him for referring to the work of Germans or Russian emigres.

Muller eventually left the Soviet Union in 1937 and spent eight weeks in Spain

helping the International Brigade develop a method of obtaining blood from

recently killed soldiers to use for transfusions. He then moved again, this

time to Scotland and worked at the University of Edinburgh continuing with

X-rays and other mutagens like UV and mustard gas.

In 1940, Muller fled Scotland due

World War II to find a permanent position at Indiana University in 1945. A year

later in 1946, Muller was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work on

mutation-inducing X-rays. He seized this opportunity to continue pressing for

more public knowledge about the hazards of X-ray radiation. Hermann Muller

increased his stature to speak out after the dropping of atomic bombs on

Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1945.

Throughout his career, Muller

advocated for the education of the public by scientists. He felt that it was

the responsibility of scientists to educate the public on their research or on

pertinent topics. Muller fought against the Texas school board’s attack on

evolution. Hermann Muller often was faced with strict criticism for beliefs,

yet he advocated for scientists to speak out on topics and to not be afraid to

use their voices.

He did promote the view of eugenics, but he

criticized the American eugenics movement for its racism and classism. He

recommended voluntary reproduction through artificial insemination for families

with genetic disorders. He supported “positive” eugenics such as the use of

reproductive technologies such as sperm banks and artificial insemination but

wrote that “ Any attempt to accomplish genetic improvement through dictation

must be debasing and self-defeating”.

Hermann J. Muller died on April 5,

1967 due to congestive heart failure.

I find Muller’s call for

scientists to educate others on their findings to be valuable and vital for the

discoveries of scientists to fully reach their significance and potential. It

isn’t until the knowledge is understood by others, especially the general

public, that we can say that the finding has reached its true value. It allows

people to act on the knowledge for positive change. This can be carried beyond

merely informing the public to involving them as seen in the ideas of Citizen

Science that were discussed a few weeks ago by Dr. Haynes. Involving those influenced

by the issues provides a more direct source to the problems, resulting in ideas

and opinions for solutions from those actually experiencing the problem.

Muller additionally told his students to bear

witness to and to speak out against the abuses of science in their generation. He

argued that genetics was the most subversive science due its basis being

fundamental to human nature and for that we must take the most ethical and respectful

approach. Muller’s continual and adamant advocacy against the dangerous effects

of X-rays is admirable and crucial to our current precautions surroundings use

of radiation. Muller’s insight into genes as individual molecular units was

influential and spurred the development of molecular biology and for that, his

legacy continues today.

Works Cited

Carlson,

Elof. "Hermann Joseph Muller." Hermann Joseph Muller

1890—1967 (2009): n. pag. National Academy of Science Online.

National Acadmey of Science, 2009. Web. 26 Mar. 2015.

"Hermann

J Muller." GNN - Genetics and Genomics Timeline. Genetics News

Network, n.d. Web. 26 Mar. 2015.

"Hermann

Joseph Muller". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica

Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 26 Mar. 2015

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2015. Web. 26 Mar. 2015

"Hermann

Muller." Hermann Muller. Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory, n.d.

Web. 26 Mar. 2015.

"Hermann

Muller." Hermann Muller. Cold Springs Harbor Laboratory, n.d.

Web. 26 Mar. 2

"Hermann

J. Muller - Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB

2014. Web. 26 Mar 2015.